The modern, cosmopolitan city is one of humanity’s greatest accomplishments, and its increasingly the environment in which much of our species lives. In 2017, its time to push back against this narrative that the rural areas of a country are more “authentic”.

In recent years of politics in the west and elsewhere, it has become trendy among the right-wing to bemoan, fear, demonize, and lament the influence of the “Cosmopolitan Global Elite”. Perhaps this is most evident in the current political climate of the United States, but elements of the rhetoric are present all over the world, both in western and non-western countries. It is a trend that has accelerated and become more clear with recent years, and received a lot of journalistic coverage after Donald Trump was elected to the US Presidency.

I’m not one to argue that people in liberal-minded people cities should ignore the rural working class, as some have suggested. Because in a functioning world, there must be a healthy sense of trust between urban and rural folk. A society cannot function if the different places that are of importance to it are taught to despise one anothers’ way of life. And in no way am I suggesting the struggles of anybody in rural regions of the world should be ignored, or that rural areas are not worthy of respect. Quite the opposite. I have tremendous appreciation for rural areas, where nature is accessible and the pace of life is slower. But I also have respect for these “elite” cities that the political right seems so intent on demonizing.

Here’s the thing – the populations, tourist numbers, GDP percentages and numbers of great educational institutions say it like it is – cities are awesome. Let’s face it, for all the struggles that certain cities have had, whether it be pollution, poverty, or education systems – the 21st century big city is a beautiful, functioning, and complex organism of civilization, which, in most of human history, would have seemed like a science fiction dream. Many people are choosing to live in cities for good reason. The majority of people now live in cities, and they generate the majority of many countries’ GDP. The young folks, patriotic or not, who want to work for their country’s biggest companies or work in their nations’ governments don’t stay in small towns, they often move to cities.

Cities’ greatness can be summarized in far more depth than what is offered by just GDP percentages. Every great global city is a distinct microcosm of a society, a group of people living and working in close proximity for each others’, and thus their nations’, and the world’s benefit. A truly great city is a forge of great architecture, arts, cuisine, and learning. And despite their commonalities, the way many cities are built can reflect the unique history and values of the civilization that built it. European cities reflect what is great about Europe, with their densely populated historic districts, public infrastructure and sense of togetherness. The office parks and private suburban cul-de-sacs of US cities may be ugly and wasteful, but they are home to many of the world’s most important businesses, and like anywhere, they reflect what their society values – privacy, prioritization of work ethic, and convenience for the individual. The neon-lit megacities of East Asia may seem on the surface like the cliche of cities from a science-fiction film, but in the way their streets retain older patterns despite needing rebuilding, and there are the ancient principles of Feng Shui that still influence Chinese construction, these cities too show what is valued in their societies. Urban Planning also reflects history. Cities with eventful histories show it in their variety of architecture, street planning, and usually both of these things. There’s the multi-layered and culturally complex cities of India such as Chennai, where colonial forts lie alongside neighborhoods were some of the oldest civilizations in Asia existed. Point is – cities arguably reflect a culture just as much as any rural area. But in a different sort of way.

Even so, In a lot of discourse surrounding the state of the world today, there’s an undertone that the rural area of any country has more of its “true authentic culture”. This idea that the rural regions are the true soul of a country is still implied and sometimes openly stated, including in travel literature, and the thing is that it’s simply wrong. It also embraces the notion all culture worth understanading comes from these rural, conservative regions we see as time-capsules to the past. At its best it is naive and ignorant, and at its worst, it is dangerously nationalistic.

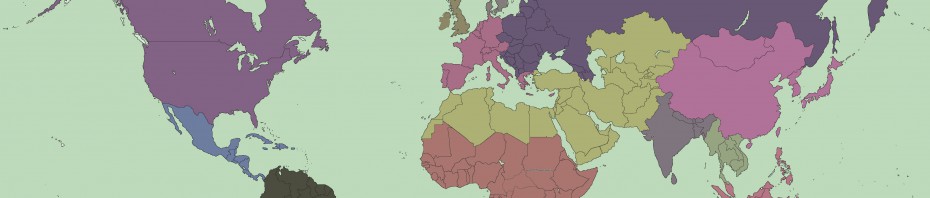

Sheer numbers alone show it to be false in many cases. The majority of Americans (80%) and citizens of many European countries live in cities, and increasingly, more and more people in the developing world do too. So, cultural values non-withstanding, if so many more of a country’s people live in cities, why is there still this undertone that the rural folk are more representative of the culture?

It often goes along with anti-immigrant rhetoric. The idea that a white guy who works on a farm in Missouri is more “American” than a second generation hispanic immigrant is based on a racist notion of “Real America”, as if the popular perception of the “good old days” is the basis of America’s national identity, and any major changes since the “good old days”, whenever they may be, is a betrayal of that “culture of real America”. Also, this mentality erases the long histories of immigrant communities that go back longer than right-wing media would have one believe. Islam in Europe as well as Latin-American and Asian cultures in the United States have long histories which have impacted their continents in far more ways than one would assume. They also were, in some cases, the original creators of what we consider to be western cultural icons. You know the classic rugged individual All-American cowboy? Mexicans were the first people in North America to have that lifestyle and culture. And most likely, a large number of white Americans who wear cowboy hats don’t know this. Filipino and Chinese communities have been in America since the mid 19th century. In post-Medieval Europe, a large number of mathematical and scientific advancements were built on, or heavily influenced by, the tools developed in the Arab World (such as algebra). That’s not to say that any Western cultural Identity is completely unoriginal. But it’s important that we acknowledge the contributions of immigrants to our icons of “real” national identity, be it in lifestyle, arts, education systems, and cuisine. And where do many of these newcomers move to nowadays? The cities.

Sometimes I am challenged back by someone saying rural areas are more culturally distinctive, and that it is more common for people to eat tradtional food, wear tradttional dress, and go to church/temple/mosque/shrine in a rural area of a country, and therefore a rural area is more “in-touch” with its national identity. This often is coupled with an argument implying that, because western fast-food joints and famous chain hotels dominate parts of many cities, that urban areas all over the world may as well be one “elite” culture.

On a surface level, yes the main boulevards of many western cities may look similar. Yes, you can find McDonalds in many places, as well as lines of storefronts selling well-known clothing brands. But to judge the whole culture of modern cities by stores a tourist may observe on the surface is a big leap. Each city’s distinct layouts and street pattern arguably has a far bigger effect on lifestyle and tourist experience than the fact that many cities have McDonalds. These deeper differences go beyond the types of historic sites. Cities’ traditional identities have long legacies which affect their economies today. Sure, San Francisco may now have more chain stores and bland condos than it did in the 60s. But in the way of the fast-growing tech industry, attracting optimistic young people who hope to change the world with their apps, its legacy is one of social disruption and boundary-pushing as much as it ever has been. It just takes on a different form than it did in the 60s and 70s. Even if a adventurous traveler tourist may bemoan the fact that a McDonalds is right next to the main train station in Florence, the fact remains that many students from across the world go to Florence to study art. Cities’ economies also are very different, and if anything, industry clustering has increased in recent years, not decreased. Cities are not the same. And it is not just economic. Far from being a homogenizing force, multiculturalism arguably makes cities more distinctive. Turkish Immigrants growing up in London have a different culture and different experience than Turkish immigrants growing up in Berlin. The diversity of ethnicities in cosmopolitan cities varies tremendously from city to city. To look at Paris and London as being the same (besides the obvious difference in language), due to both of them having McDonalds and both having a number of ethnic enclaves, is a notion that does the inhabitants of those cities a huge disservice.

Ultimately, the divisive politics that have dominated the US and Europe boil down largely to geographic divides, and one of the strongest is the urban-rural divide, perhaps most obviously in the US. Even if rural and urban folks don’t agree with one anothers’ values, lets be sure that we don’t let them define the other by a cultural reputation they don’t deserve. Just as rural places are not entirely made up of dumb hicks, cities are not full of scheming elitists who think that everyone else is below them. In our world, we need to do a better job at giving other living environments the respect they deserve, even if we don’t always share compassion. Cities do not get a lot of respect in American political discourse these days, and when we write about cultures and travel, perhaps its time to stop enabling the “rural areas are more authentic” narrative. Both urban and rural environments are representative of their national culture in their own ways. So let’s stop acknowledging the “authentic culture” in just the latter.